I went to my first playgroup in 2021. Someone made me a cup of tea and offered to hold my newborn while I played stickle bricks with his big brother. We could eat endless custard creams and the crumbs fell into someone else’s playdough. My one-year-old lost his mind during the ‘hop little bunnies’ dance at the end of the session. I had a great time.

But something started to feel kind of Truman show-esque. After a few weeks, I realised that everyone else there knew each other and were in on something I wasn’t. As Christmas approached, I started to get given leaflets on my way out the door inviting me to Christingle services. Santa visited the last session of term and gave my kids bubbles, and me an invite to the alpha course.

As my second maternity leave wore on, I began to search for place I could eat custard creams without the covert evangelism. My research turned up four kinds of playgroups within a 5 mile radius from our house, ie. in the city centre of Sheffield.

1. Church playgroups. These made up 70% of provision.

2. Council-funded playgroups, in libraries, family centres, and at two adventure playgrounds, funded by Sheffield city council. This was about 15% of provision.

3. For-profit playgroups, mostly around music and movement. This was about 10% of the groups near me.

4. Then - at just 5%!! - what I’m calling community playgroups, run by volunteers not and attached to institutions. These tended to be in affluent, left-leaning areas of the city. (Meersbrook is the community playgroup capital of Sheffield.)

This remaining 5% was how I had imagined playgroups would be. Indeed, in 1980, there had been 150, 000 of this kind of community playgroup, serving half a million preschool children across the UK. I’ve been meaning to write about where playgroups came from and where they went ever since I started this – now very irregular! – newsletter. It’s only now that my eldest has stopped bunny hopping and started school that I’m getting round to it.

Playgroups have their origins in the Blitz. Many parents of young children refused to send them away from home and so, in razed cities, charities like Save the Children set up safe, daytime spaces where children could play after a night of bombardment. But, after the war, young children were pushed out of public space. The architects of the new welfare state believed that happy babies needed to be with their mothers, and that good mothers needed to be at home. Universal child benefit and full male employment in jobs which paid a so-called ‘family wage’ were meant to prevent women seeking work outside the home. The new raft of social housing which followed the war was meant to create nice homes to stay in, with indoor bathrooms, cosy living rooms, and front doors leading onto pavements wide enough for prams.

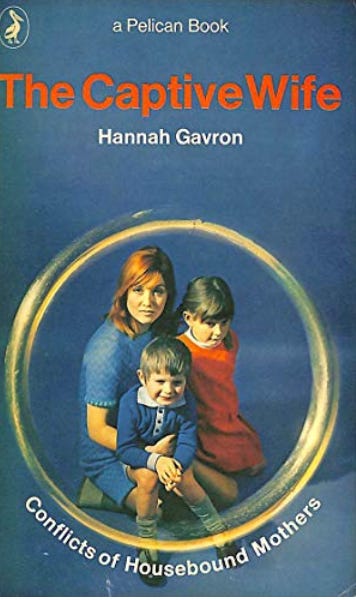

But however nice these new homes were (and they often weren’t), they were also lonely. In 1965, a university lecturer turned housewife named Hannah Gavron died by suicide. She had written a book, The Captive Wife, that outlined the crushing isolation of mothers living in new suburbs and housing estates. Looking back on the origins of the Playgroup movement, its founder Belle Tutaev pointed to The Captive Wife: it described perfectly the isolation she too had felt as a young mother in the early 1960s. ‘It was’, she would later proclaim, ‘never part of the original deal for mothers to have babies instead of the rest of the human race’. Her solution was play.

In 1961, Tutaev had organised a petition, delivered to the education minister, demanding more play facilities for under 5s, and collected pledges from 150 women who would start informal ‘playgroups’ in their communities. These new playgroups would give children a space to play, outside cramped houses and away from fast cars, and give their mothers a way to make friends. Even more crucially, wrote Tutaev, playgroups would give mothers a chance to see other children the same age as theirs making mess, throwing tantrums, and causing havoc. This would reassure them that they, and their children, were normal and not alone.

One of her collaborators remembered arriving at Belle’s playgroyup in East London: My forth child had just been born when we moved to a new house on a new estate - at first it was wonderful but after a few weeks all I could think was, where is my mother, my sisters, my cousins, my aunties? Nothing - nothing but children, breakfast, lunch tea and supper. Measles, mumps, coughs, months of isolation. When did I last have a bath? Go to the lavatory with the door shut? There were points in my second maternity leave when (if you switched ‘measles’ for ‘covid’) I could have written this.

Belle Tutaev’s first playgroup functioned as a co-operative. Parents clubbed together to hire a space and solicited donations of toys. The playgroup was volunteer led, with mothers taking turns to set up and pack up.[1] Tuteav’s playgroups had a clear educational philosophy: that free play was the best way for under 5s to learn. This play based pedagogy was fashionable in left wing child development circles at the time, and it suited a non-expert organisational model. Adults would provide the space and the materials; children would do as they pleased. By 1965, the year that Hannah Gavron died, there were over 300 playgroups in England alone, affiliated to the Preschool Playschool Association, headed by Belle Tutaev.

The Preschool Playgroup Association also had a social philosophy: it wanted to establish ‘contact between the world of the adult and the world of the child’. Just as a mother would benefit from seeing a child play with their peers, so too would a child benefit from seeing their mother with hers. At playgroups, mothers were busy and important, surrounded by other adults. More, Tutaev believed that if a child could see their mother pouring squash for their friends, then they would realise that what their mother was doing was work, and that they – the children – were worthy of this labour. This was, to my mind, the most radical aspect of the playgroup movement: it made maternal work visible through child’s play by bringing both out into public.

The Preschool Playgroup Association had a complicated relationship to feminism, mostly because feminism in this era had a complicated relationship to children. On one side, many feminists found ideas about maternal attachment empowering. They wanted to reclaim motherhood as a sacred, vital state. But elsewhere in feminism, there was a growing anti-maternalism: women wanted to enter the world and the workplace on equal terms with men, and saw motherhood as a hindrance. The Playgroup movement’s feminism was a pro-child, maternal feminism. While it sought to liberate mothers from the home, it saw women’s liberation inherently bound up with the liberation of children. Tutaev and her allies wanted to build women’s confidence and to expand their social and professional horizons, but not remove them from their children in order to do so. The Preschool Playschool Association differentiated itself from a feminist lobby for nursery schools: while it wanted children to have greater opportunities for play it wanted to do this without ‘neglecting them’ . It was critical of the 1977 Trade Unions Congress charter for under 5s which lobbied for nursery schools that mothers could leave children at while they went off to work. This, it claimed, was treating children as an ‘economic problem rather than as people’.

The playgroup movement in the 1960s and 1970s was antihierarchical. Playgroups were rooted in communities: living locally and bringing your own children was a precondition to involvement. It quickly grew beyond its middle class origins. A survey of playgroup attendees in 1975 found that 60% of the families had male workers in manual and traditional blue collar jobs. A further 10% were unemployed. Committee positions were to be held for no more than 3 years (‘a year to learn, a year to do, a year to find a replacement’). There were only a small number of volunteers in a national ‘head office’, which for most of the 1960s and early 1970s operated out of Belle Tutaev’s living room. These ‘head office’ volunteers could be invited to local playgroups, and it was considered best practice to defer to local mothers. Recalled one: I arrived at a Playschool in east Sheffield to find children swinging from a crucifix, jumping from the pulpit, crawling under pews. After 30 minutes the mothers called time, and the children settled down to their calm play. The mothers - all of whom lived in small flats in nearby council housing - knew that their children would need to blow off steam for half an hour before they could play.

At national playgroup congresses and training days, mothers were known only by their first names. They simply played together, often unsure of who exactly was leading the sessions. Playgroups themselves were run on a strictly voluntary basis. Most playgroups allowed mothers to leave their children for up to three hours at a time – operating a rota system for staying to play and free time away. It was only playschool chairs who had to attend every session. In some playgroups token payments were made to chairs. A typical sum was the cost of taking the weekly laundry to a laundrette.

Empowered by their experience of local organising, from 1970 the Preschool Playgroup Association began direct government lobbying for additional funding for under 5s. This was granted from 1977, but with it, more stringent conditions for the regulating and organisation of playgroups. Where playgroups received funding they became subject to local council inspection and the credentials of chairs, and the number of toilets per child. The suitability of ramshackle scout huts and church halls were scrutinised. Chairing a playgroup became more arduous: volunteers began to decline.

By its own telling, the Preschool Playgroup Association was a ‘victim of its own success’. It has given mothers a level of confidence which led them back into the paid workplace and, as such, there were fewer volunteers. Children needed longer hours at childcare than the typical playgroup (which usually ran 9am-12pm three days a week) could provide. Of course, it was not actually the playschool movement that created the gradual exodus of women from say-at-home parenthood: this was a result of feminism, in part, but also the changing economy. Mass male unemployment and the rising cost of living from the 1970s meant that more women needed to work to support families. As membership declined, the Preschool Playschool Association became more focused on lobbying for increased state provision for under 5s and less on local organising. In 1992 was fully transformed into what is now the Early Years Alliance : a professional lobbying body for early years workers in nursery, child-minding and preschool settings.

I have a pamphlet of all the playgroups that existed in central Sheffield in the mid-1980s from the City Council archives. There were nine, all affiliated to the Preschool Playgroup Association, where children could be left for up to three hours for a small fee, ranging from 30p to a pound. Some had registers of regular attenders (like the University Playgroup situated in a church next to campus on Upper Hannover Street) while others had a much more informal drop in policy (like the two ‘Shoppers Playgroups’ in the city centre, for the children of parents doing errands in town). This pamphlet also lists what were known as Mother-and-Toddler Groups – the more familiar stay-and-play in a church hall model that exist now as ‘playgroups’.

A playgroup in Broomhall in 1977, which no longer existed in 2000.

Thanks to archive.ph it’s possible to reconstruct the playgroup scene in Sheffield in the early 2000s. By then, all but one of the old-style playgroups has disappeared, while the list of church-hall Mother-and-Toddler Groups had expanded. This isn’t a coincidence. In response to declining church attendance, and a global rise of charismatic Christianity, the Anglican church proclaimed that the 1990s would be its ‘decade of evangelism’. This evangelism would take a new form, quite unlike the Billy Graham style mass preaching events of the 1960s and 1970s. People would be invited into church spaces to experience community in the form of playgroups, elderly lunch clubs, and afterschool youth provision.

A dynamic where churches stepped in to fulfil the former functions of the state was widely written about in the early days of austerity. Foodbanks are the classic example. It’s much harder to talk about the religious takeover of playgroups, which happened so long ago that many parents won’t remember a community-led alternative. (My kids, at least, are second generation church-hall playgroup attendees: some of my very earliest memories are of orange squash and digestives in the basement of Southbourne Methodist Church.) The story is complicated because churches aren’t ‘taking over’ from the state in any straightforward state, but the church takeover of playgroups is nonetheless a product of one aspect of neoliberalism: the increase in state-led regulation that took place alongside the shrinkage of the state itself. The Thatcher government created stringent health and safety guidelines that shut down playschools situated in crumbling scout huts, while failing to fund shiny new alternative forms of care. It changed the economy in ways that meant more women needed to work, and fewer could give up time to roll playdough and pour orange squash.

Maybe the loss of community playgroups is an ambiguous one. One the face of it, the kinds of women who might have run them have gained something better: access to a world beyond the home without their children in tow. Like Hannah Gavron in 1965, I have two sons, aged 3 and 4. Unlike her, I can lecture at a university while being their mother. I can, apparently, have it all. Belle Tutaev and the other founders of the Playgroup movement assumed that, were mothers to be working outside the home, they would not need access to the social world of the playgroup in a way that their stay-at-home counterparts had. This isn’t true. A friend I met in a baby sign class has been working on an incredible project on perinatal loneliness since having her own child: even though more mothers then ever work, early motherhood is still profoundly lonely.

When I wrote this newsletter more regularly, I often ended posts with a vague implication that we should nationalise lost some aspect of early childhood: crèches, soft plays, a network of childminder-nurses who could be deployed to houses in the event of chickenpox. But if we want the old style playgroup back – the playgroup that built communities, that gave parents time for leisure not labour, that radically prioritised play, that respected the expertise of parents above the rigours of professional inspection – then the state is not the answer. Community is. But, if we wait for the state to produce the right conditions to build community in, it will never arrive.

‘child led’ play for my three year old is all potions, all the time

I spent an hour before I started work on Monday in a scout hut. Electric heaters hummed, all the lights were on, and weather-warning level rain was hammering on high windows. I was with my three year old, kneading freshly made playdough scented with cinnamon, at the only Sheffield playgroup that has survived from the 1970s until the present day. It’s still run by a committee of parents, though its now called a ‘playschool’ and the sessions are led by paid professionals rather than volunteers because most of the parents whose children go are, like me, on their way to work. This year, I became the chair of the playgroup’s management committee.

I love our playschool because – despite the administrative constraints of OFSTED and the financial constraints of the current childcare funding system – the ethos of the 1970s playgroup movement still exists. Here, in 2024. It’s all play, all day, led by children and – via the management committee - their parents. I’m not sure I have time to be the chair, but I don’t want to spend my children’s early years only mourning what has been lost. Rolling cinnamon scented playdough in a scout hut at 8:30 on a Monday morning is my attempt to have it all.

[1] Dads where they were involved did DIY and, very occasionally, came to play sessions to ‘do rough and tumble with the older boys’