Reading Penelope Leach in Lockdown

babies, care work, and lost archives

In the first lockdown, I often struggled to sleep. I would get up, make myself a hot chocolate, and take it back to bed with me while I waited for whenever the baby would next wake. I would also take a book: Penelope Leach’s Baby And Child.

First published in 1977, Baby and Child - from birth to age five, has sold over two million copies, and been reprinted five times (most recently, 2022).[1] It’s author, child psychologist Penelope Leach, was born in Hampstead in 1937, the daughter of two novelists. With a degree from Cambridge, and a PhD from LSE in child psychology, her career began at the Home Office studying juvenile crime. Her passion, though, was the development of the ‘normal child’ and their family. After Leach had her own two children in the mid-1960s she began writing about parenting for a popular audience. At first glance, Baby and Child feels like a medical reference book. Divided into 5 sections, from newborn, settled baby, toddler, preschooler, and the school age child, it appraises parents of developmental norms, and offers practical advice - often with careful diagrams - for tasks ranging from nappy changing to nail clipping. These sections hang together on a basic principle: that parents should enjoy their children. The relationship between carer and child should be one of mutual satisfaction, and a family should strive for child and adult happiness simultaneously.

The copy I have is from 1988, the edition that my mum referred to as she raised me and my younger brothers. I don’t know if the sense of familiarity I feel when I read Leach is because of this, or it is a more aesthetic resonance. The photos, by photographer and child welfare advocate Camilla Jessel, have the candidness of family albums: she captures the stoicism of tired mothers, and the concentration of young children especially well. Reading Your Baby and Child slowly and deliberately through lockdown fulfilled my need to see baby care described as I learned it in isolation. But, more than that, reading Penelope Leach began to change the way I saw the relationship between the personal, professional, and political, as a historian of childhood with a very small child.

image from the 1988 edition, that look of glazed vigilance feels really familiar to me

My 1988 version of Leach shows its age: it assumes the heteronormativity of families and speaks of mothers returning to work as though it were a choice rather than an economic necessity.[2] But there is also something about the 1980s version of Leach that I find appealing. Baby and Child was written before hard lines were drawn ‘mummy wars’ that have characterised the last two decades of parenting. Leach is not preoccupied by questions of being ‘baby-led’ or routine driven. Rather than promoting a particular ideology, her everyday advice was a conscious act of conciliation between the psychoanalytic tradition and the feminist movement. Trained at the Tavistock Clinic, Leach learned from wartime psychoanalysis John Bowlby whose name would later become synonymous with his ‘attachment theory’. This was that infants, by evolutionary necessity, had learned to form close bonds with those who cared for them. These bonds were based on nutrition and pleasure (for Bolwby, this meant ‘the breast’) but also attentiveness and affection. Children who did not have a chance to form these bonds of attachment or had those bonds interrupted would suffer psychological scars in later life. Held aloft as evidence were the various child victims of the Second World War - orphans, refugees, evacuees - and their trauma.

Leach believed that Bolwby’s attachment theory had been co-opted in a way that robbed it of nuance and emphasised ideas that Bolwby himself would later come to question. Foremost among these was his theory of maternal deprivation. Maternal deprivation was the anthesis of secure attachment - the damage that would occur if the mother was absent, or bad[3]. Maternal deprivation had, Leach argued, been seized upon by postwar policy makers to suit the needs of modern capitalism. Women had to stay at home to care for children, freeing up jobs for men and enabling their long working hours. This was bad for women, who ended up isolated and frustrated in the lonely suburbia of the 1950s. It was no wonder, then, that the feminist movement felt it had to reject attachment to liberate woman from the confines of care work. To free woman, they had to insist that mothers’ relationship with babies were unimportant.

Leach’s works, in my reading, are an attempt to insist on the importance of care work without imprisoning women. She imagines a world where the interests of women and children might not feel antithetical, but mutually supportive. She doesn’t reject Bowlby, but insists on the difference between maternal deprivation and maternal separation. Babies and mothers can, and indeed should, spend time apart, and a baby’s primary carer does not need to be its mother or indeed a woman. They need only be consistent and attentive. They also need to be supported. In Baby and Child Leach gives women practical advice for creating sustaining communities around them. Elsewhere, she argues for wages for breastfeeding, high rates of maternity pay, and universal free childcare. I’ve seen Leach described as a child centred feminist. I think she could as easily be described as a care centred child right’s activist. She sees both the value of care to the cared for, and its cost to the caregiver. Children have a right to care, and society must compensate those that do the work.

In lockdown, the needs of children were sacrificed for the needs of elders, and the needs of mothers simply did not exist. Reading Leach at that moment felt like a political project. It was also a personal one. My mum died when I was pregnant with my first son. I can’t ask her how she was influenced by Penelope Leach, which to be honest is pretty far down the list of questions about parenting young children that I wish I could ask her. Working out how I want to parent, what I want to take and leave from my own early childhood, has often felt like doing history with a redacted archive. I’m always trying to find ways in from the margins, read against the grain. I look at old photographs and hunt around my childhood town on google maps trying to get a sense of what her life was like with her as very young children, and what she would think of mine. I wonder, too, what my children will remember about life when they were very young, especially if I am not there to tell them.

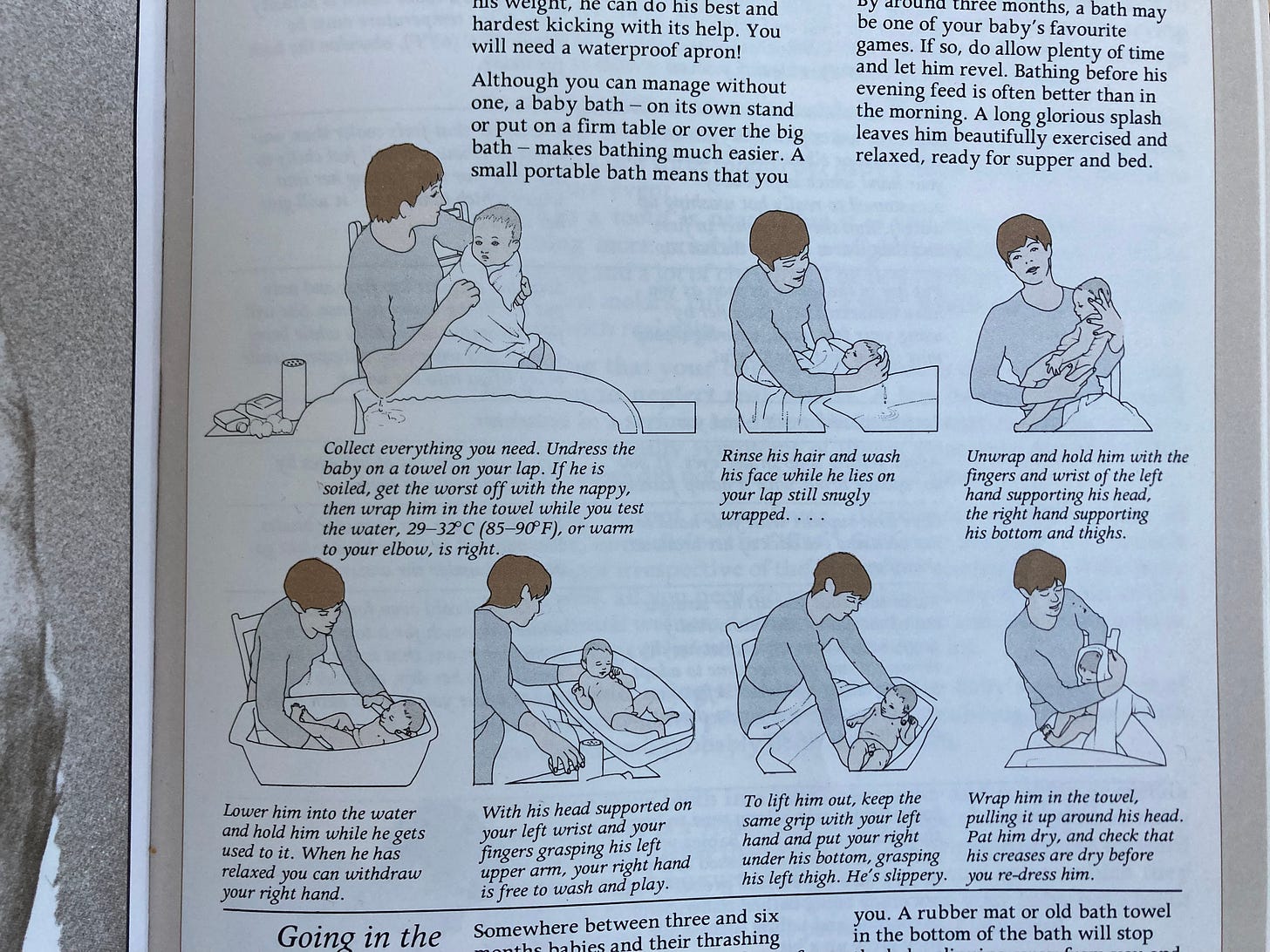

This isn’t just mine, the problem of my personal missing archive. It’s the whole challenge of doing the history of care work and the history of childhood. We have access to expert texts, like Leach’s, and we can know if people bought them. These texts might shape big decisions you make as a parent or experiences you have as a child. (Childminder or nursery, for example, is something that Penelope Leach has views on.) But parenting, like all interpersonal relationships, are a series of rapid-fire micro decisions and interactions. These can’t be captured by advice on how you ought to parent. More, infant care work, historically women’s work, is by its nature self-obliterating: the baby is hungry again, the nappy is wet again, the baby is awake again. There is no product, the labour disappears. Feeding, changing, shhh-ing, the stuff of cabbages and habits, is rarely written down.[4]Leach does capture some of the mechanics of this labour, but already her how-to diagrams of washing a newborn baby feel removed from anything I have ever participated in, as either washer or washed.

bathing a newborn, 1988 edition

If the written archive is not enough, or does not exist, how do we recapture those caring or cared for memories from the haziness of infancy or exhaustion of new parenthood? Penelope Leach herself has views on this: the role of intergenerational transference had been under-appreciated, and so the role of advice had been overstated. The way that we were cared for will show up in the way we care when we’re not actively seeking otherwise. I’m not suggesting, and neither was Leach, that children are essentially being raised by their grandparents, residing in the personage of their mum or dad. I am suggesting, though, that care work – because it is rarely explicitly taught or written down – might hold an archive of its own as ways of doing and being seep down through integrational networks.

In searching for my redacted archive, I’ve become especially attentive to the moments that intergenerational experience creeps in. It’s never in the intentionally puzzling out what my mum would have done that I get the best access to it. Instead, it’s in a lullaby forgotten until 3am one wakeful morning, a particular way of stroking the napes of my sons’ necks, the evocative smell of sudocream, bringing back the way she lifted my brother’s legs to baste his little bottom. When I’m not trying to remember, but simply do, I find my way into the inaccessible archive of early memory.

The psychoanalytic tradition that Leach hails from has a lot to say about early memory and its lack, infant amnesia. For Freud, early memories were repressed because of their connection to taboo sexual desire. For Melanie Klein - far more of an influence on Penelope Leach - infant memories were not so much repressed as inaccessible because young children were prelinguistic and lacked a theory of mind. Their memories were likely to be feelings rather than thoughts, from a moment in life when they could not separate themselves, or their emotions, from the people around them. Trying to access early memories was a murky business. As soon as they were expressed linguistically, they were corrupted, as likely to be fantasy as fact. And yet, for Klein and the child psychoanalysts that followed her through London’s Tavistock institute - Bowlby, Winnacott, and later, Penelope Leach - early experiences were never fully forgotten. They were the foundations on which all personhood was built. Even is the archive was redacted, it still existed. What was written underneath the censorship of age, language, fantasy, or taboo, mattered.

Historians don’t have to take everything from child psychoanalysis to recognise its use. Like Leach, we can reject the theories of maternal deprivation that harmed women’s liberation while still insisting on the importance of early experiences of care, and by extension care work. If we do so, we need to be alive to new possibilities for reading people’s redacted personal archives. To take Penelope Leach seriously is to embrace how limited her writings on both are as an isolated primary source, and instead to try to account for intergenerational transference and the importance of deep, synaptic memories that are not attached to words. We need to think about other ways of remembering, and other ways of knowing.

Perhaps what I find so deeply soothing about Baby and Child is not what it says, but how it feels. At a point when most of my parenting advice comes through a sterile, fluorescent phone screen, I’m comforted by its hard back, glossy dust jacket and thick card pages that speak of childhood encyclopaedias. Its heft and its images of late 80s mothers lend it some of the maternal authority of my own. In the absence of the archive I want, I’m grateful for it.

my copy - with a little splash of lockdown hot chocolate in the bottom left corner

PSA: everything on this substack is free to read, but you can buy me a coffee or contribute to my childcare costs here if you’d like: https://ko-fi.com/emilybaughan

[1] (this makes it Britain’s single bestselling childcare advice book)

[2] Leach herself admits that the old editions are no longer ‘fit for purpose’ https://www.nurseryworld.co.uk/opinion/article/penelope-leach-on-why-she-has-updated-her-best-selling-book-for-parents

[3] Other psychoanalysts - Harry Harlow with his wire monkeys, and James Robertson with his Two Year Old Goes to Hospital, illustrated this paradigm with devastating effect, lodging it in the public consciousness

[4] read this beautiful poem https://www.tumblr.com/missedstations/188019607520/in-the-mens-rooms-marge-piercy

This was a really interesting read, thank you! And a fun "coincidence" (thank you algorithms) that your post popped up in my feed just this week, as I, just last weekend, came across an old copy of the same book but in Finnish translation, in my mother's bookshelf, and promptly borrowed it, expecting to read a lot of outdated advice about not hugging your kids :P I was happily surprised when I started browsing through it, and got intrigued about what else I have been too black and white about in my understanding of the history of parenting instruction :D