In my local supermarket, formula milk is security tagged. Baby milk is now one of the most shoplifted items across the UK. Newborn milk costs between £4 and £10 per day. Prices have leapt by almost 25% in the last three years. Many foodbanks have policies that prevent the distribution of infant formula. Universal credit, healthy start vouchers, and other forms of state assistance don’t come anywhere close to covering the cost of feeding an infant.

From 1940 until 1976, baby formula was either free, or heavily subsidised by the state. Parents of under ones were issued tokens which could either be swapped for formula directly at their local infant welfare clinic or, if they were wealthier, used to purchase formula at around a quarter of the market rate. In 1976, this was usually 20p per pound, versus 65-80p for a pound of unsubsidised shop bought baby formula.

On his fifth day of life, my second baby fed for 17 hours out of 24. I first learned about National Milk listening to the audiobook of Deborah Orr’s Motherwell while I was feeding him. In the mid-1960s, Orr’s mother, too, had hunched for hours over an insatiable baby boy. Orr recalled her gruff Glaswegian father pronouncing, ‘this is no good Win’, then skulking off to the welfare clinic to get free National Milk. I was fascinated by the idea of not just free but state sanctioned formula milk. When I had suggested to my midwife that I might ‘top up’ my ever-hungry baby with formula, she had looked aghast. He was gaining weight; I should keep going.

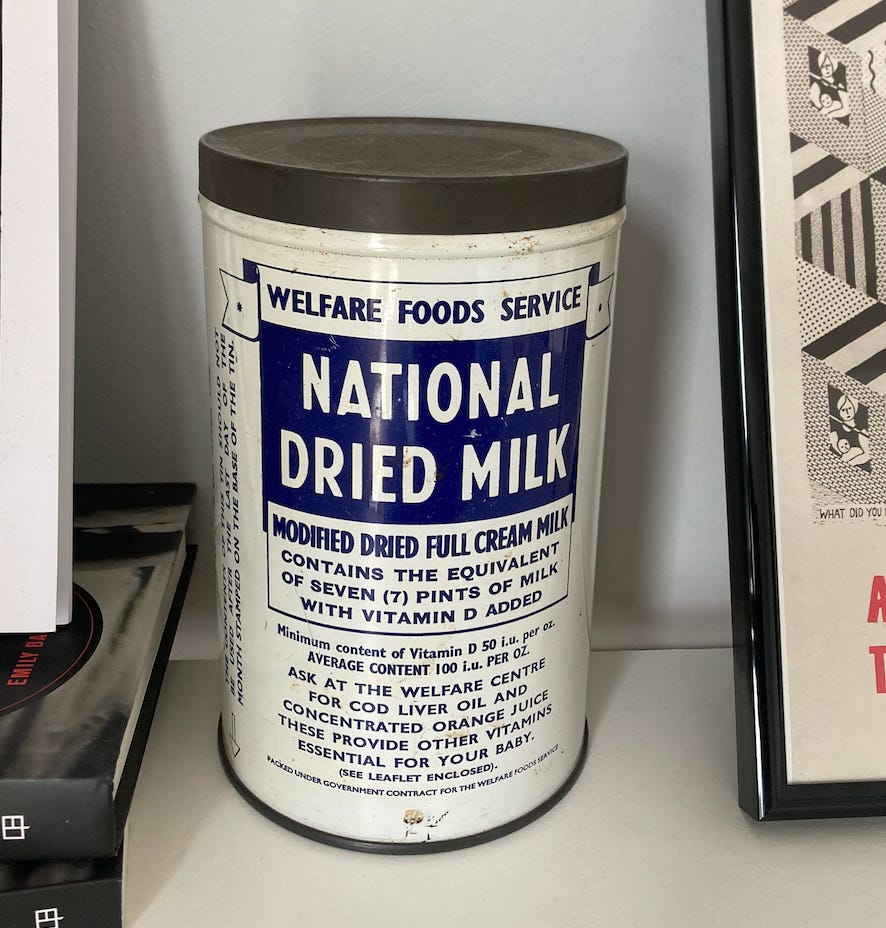

£21.99 on eBay

Months after this conversation with the midwife, I bought myself an empty tin of National Milk on eBay. It sits on top of my bookshelf, and I sometimes look at it while I write. It’s a pleasing object. It satisfies my invented nostalgia for a utilitarian, mass produced era before my own childhood. It’s colour palate pre-empts the blueification of the National Health Service in the 1980s - but speaks already to the connection between navy blue, the authority of the state and the sterility of health. It feels reassuring, approving, even. Here is the milk of the nation for your child. The tin reminds me, also, of my entitlement to orange juice and cod’s liver oil which can be collected from my local welfare clinic.

Beyond Deborah Orr and my bookcase, the only other tin of National Milk I’ve encountered is in the Wellcome Trust’s MILK exhibition, which I visited couple of weeks ago: a whirlwind tour from wet-nursing to white supremacy. Before the invention of formula milk (1865, the exhibition tells us) it was not the case that all babies were breastfed. Those not fed by their mothers, or wet-nursed, relied on animal milks, porridge, water, and sugar. Many died. During rationing in the Second World War, the state took control of dairy production and distribution, with rationing equalising milk access. Under 5s, pregnant and nursing mothers were given special allowances, and their milk was subsidised by the state. Fresh milk was increasingly turned in to powdered milk. This kept longer and was easier to distribute. The first tins of National Milk were sealed in 1940.

Away from the front lines, war is often good for children. On the British home front in the 1940s, National Milk rapidly reduced infant mortality rapidly. After the war, distributed through infant welfare clinics along with the orange juice and cod’s liver oil, National Milk had the secondary effect of connecting families with the expanding apparatus of the new welfare state. Supplying milk in two-weekly increments meant that families returned again and again to the welfare clinic, where babies were weighed, vaccinated, screened for overall development and childhood ailments. Because during rationing, National Milk was free for all, it was not associated with the stigma and state surveillance of poverty. When rationing ended in 1953, National Milk was still free for those on low incomes and subsidised for everyone. It was being drunk by over 80% of British babies.

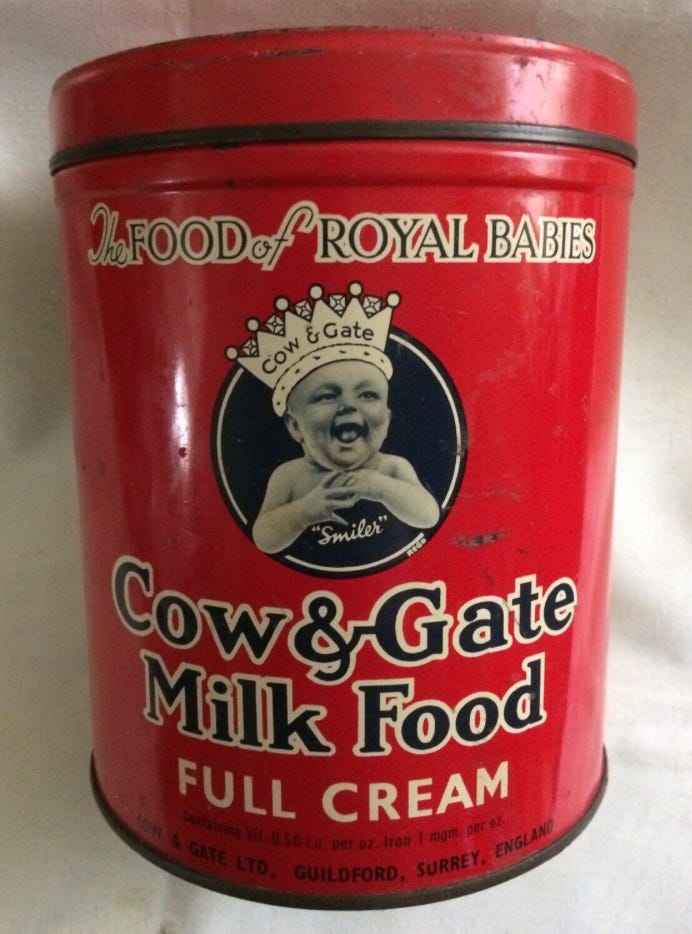

Formula milk companies were never fully replaced by National Milk and remained the top choice for wealthier families. In 1948, the infant Prince Charles was fed with Cow & Gate milk, and sales of the brand soared. Formula milk companies sought inventive ways to compete with the reassuring blue branding of National Milk, placing themselves at the centre of state provision to gain some of the reflective, reassuring glow of the NHS. From the mid-1960s, Nestlé, Cow & Gate and Johnson & Johnson began to distribute free samples of their milk to NHS hospitals. The samples they gave were, crucially, in individual, ready mixed bottles. Giving these out to newborns saved time for staff, who didn’t need to sterilise bottles, warm up water, and mix National Milk powder into it. Branded formula, rather than National Milk, increasingly became infants’ first drink. Parents carried brand loyalty, along with free samples, home with them from the hospital.

Cow & Gate, 1968. Do you want to give your child National Milk, or Royal Milk??

Formula milk is only as good as the conditions it is prepared in and the water it is prepared with. As pre-mixed branded milk crept into postnatal wards, new mothers lost literacy in how to prepare powdered milk. At the same time, advances in post-mortem examination showed that, in the cases of cot death, many babies had gathered bacterial infections that could have been picked up from improperly sterilised formula bottles and water. Pathologists also began to note the high volume of sodium in the bodies of deceased infants. Formula companies adjusted their recipes. In 1973, ‘newborn formulas’ for babies under six month were launched, with lower concentrations of salt. Reports appeared in national newspapers, linking National Milk to infant death.

Why not just change the recipe for National Milk? In the early 1970s, the Conservative Prime Minster, Edward Heath, was attemping to rationalise welfare spending. In 1971, famously, the then education secretary Margaret Thatcher ended the free provision of milk in schools. New parents, meanwhile, noted that National Milk was quietly disappearing from the shelves of chemists and supermarkets. It remained theoretically available, but its presence was not being advertised.

Then, in 1974, formula milk became international headline news. Left wing humanitarian NGO War On Want produced its Baby Killer report, revealing the practices of formula companies (in particular, Nestlé) in Africa, where free milk samples were being given to mothers of newborns (often by Nestlé representatives posing as nurses), who became unable to breastfeed and then unable to afford formula milk when free samples were used up. Babies were dying of malnutrition, or from bacteria introduced as parents mixed powdered formula in insanitary conditions. An international outcry resulted in boycotts of Nestlé, and the promotion of breastfeeding became a global health priority. In 1990, the World Health Organisation would assert that all babies had the right to breastmilk, and release global guidelines for its promotion in hospitals.

Image: Rachael Romero, for I.N.F.A.C.T campaign against Nestlé, 1975

In Britain, the new Labour Prime Minister, Harold Wilson (a founder member of War on Want) commissioned a report into ‘infant feeding practices today’, by paediatrician Dr. Tom Oppé. Published in 1974, Oppé’s reoports argued that, even in countries with adequate access to safe conditions to mix formula, breastfeeding should always be preferred. He cited concerns over sodium, and – in his view – the preferable protein composition of breastmilk. (Research into the composition of breastmilk was, at this stage, very patchy.) Oppé argued that the government should be devoting its resources not to the continued production of National Milk, but to the promotion of breastfeeding.

And so, rather than being remade, National Milk Was gone. When the last tins were removed from shelves in 1976, it was still the main source of nutrition for 70% of British babies. The Labour government claimed that it would use savings from National Milk to promote breastfeeding, and this was celebrated by pressure groups such as the National Childbirth Trust (NCT). Meanwhile, mothers cut off from National Milk quietly fretted about cost in the columns of women’s magazine. But feelings of guilt quickly replaced feelings of entitlement. If mother’s ‘failed’ to breastfeed, they broadly accepted that the cost of feeding their infants was now a private, family problem.

But breastfeeding didn’t get easier or more popular. In 1975, the most widespread (and NHS approved) breastfeeding advice remained schedule focused: the infant should be fed at 4 hourly intervals, at 10 minutes on each side and no more. This makes me wince to read: a pathway to engorgement and a frantic child. Poorly advised women continued to reach for ready-made milk. Formula companies were the ones to gain from the state-led promotion of breastfeeding.

During the 1980s and the 1990s, new research on breastfeeding (much of it observational, based on the practices of communities in the global south) changed advice. Babies fed not on schedule but ‘on demand’. As a poster on the wall of the postnatal ward I stayed in with my first baby stated: “it is always appropriate to offer the breast”. Hospital policies changed to reflect the research: instead of spending their first hours in a hospital nursery, babies began to ‘room in’ with their mothers. Continuous contact made breastfeeding more likely.

And breastfeeding rates rose. Or, at least, ‘initiation’ rates rose. In 1974, 53% of women would ‘offer the breast’ for baby’s first feed. By 2010, 85% of women did. But after this, usually supervised ‘first feed’, breastfeeding rates have remained surprisingly low. Today, 23% of babies are still being fed at 6 weeks. By 4 months, it is 18%. This is still higher than 1975 but there’s good evidence that the state halting the production of National Milk in favour of promoting breastfeeding had little to do with this. The two factors that make breastfeeding most likely are the age (older) and education (higher) of the mother. Breastfeeding rates have risen in line with increasing maternal age and education status. Low income households are more likely to rely on formula.

When I looked in the mouth of my ever-hungry newborn, I saw that his tonged was forked. The gallons of milk he seemed to consume came back up in projectile arches of white. It took access to paywalled medical journals, a drive into wilds of the peak district, and £300 to have my sicky, snaky baby diagnosed with, and treated for, a tongue tie. Afterwards, breastfeeding him became - just about - manageable. But it still was, and remains, an all-consuming lifestyle choice built into every day.

Jess Dobkin’s installation, Milk Report, at the Wellcome MILK exhibition explores feminist frameworks for the cost of milk

Histories of motherhood usually include these kinds of vignettes. I’m currently reading Joanna Wolfarth’s Milk, a history, which frames each chapter with anecdotes from her own experiences of feeding her son.1 Wolfrath’s tells us that breast is but she uses her personal difficulties to show us that sometimes it ‘doesn’t work out’ and so safe, scientific alternatives are vital. It reads as a sort of ‘there but for the grace of privilege go I’. Though Wolfrath takes care never to stigmatise formula milk, it is always cast as a reasonable but regrettable second choice.

But we don’t actually know that breast is best. We don’t know this because formula milk is inseparable from the conditions that it is mixed in, and the human error of the mixer. (One of the culprits of the sodium saturated babies in the 1970s was the widespread belief that, when mixing formula milk you should add an extra scoop ‘for the bottle’.) We don’t know this because all the outcomes-based research on breastfeeding is contextual. It is impossible to separate the benefits of breastfeeding from the relative privilege of breastfeeders. Is it the milk that proffers ‘high IQ’ (a deeply suspect measure of anything, anyway), or the conditions that made the offering of milk more likely (the older, richer, more educated mother.) When these things are factored it, the likely benefits are fractional.

And what no one puts on the other side of the balance sheet is the cost. If a newborn breastfeeds for five hours in 24 (a conservative estimate!), the mother was paid at the minimum wage for the time she spends breastfeeding, she would earn £50 a day. And this is before we total the value of the things left undone by the breastfeeding parent (paid work, or caring for an older child, perhaps.) Then, people need to eat more (ideally nutrient dense) calories to generate the milk to sustain another human life. (The fat phobic NHS spends the whole of pregnancy advising you on how not to gain weight and assumes your desire to lose any weight managed to acquire though it’s suggested pregnancy diet of wholewheat pasta and carrot sticks postpartum). Because the cost of breastfeeding is borne by women, we assume that it is ‘free’. When women refuse this cost, either willingly or reluctantly, their babies generate profit for infant formula companies whose ethical records are shady at best and cartoon-villain evil at worst.

But it’s not about the money. The ‘resurgence’ of breastfeeding took place in a cultural moment when more traditional forms of motherhood were being celebrated. A backlash against the second wave, and a response to the increasing number of women now staying in work while they had young children. The 1980s and 1990s were the era of Laura Ashley dresses (the original tradwife)2, and the popularisation of wartime theories of infant attachment through the well-read texts of experts like Penelope Leach. As women became more economically powerful, more politically visible, good motherhood became more tied to its biological functions. The promotion of breastfeeding coincided with cuts to child benefit and public services for the young. It was one of a series of cultural, economic, and political changes which served to make the care and cost of children a private, family matter.

tradwife, 1990

As a culture we want women to breastfeed because we want motherhood to be sacrificial, totalising, biological and private. In the absence of fully conclusive science, we use words like ‘magical’ to describe its benefits. But the slow-rising rate of breastfeeding shows that policies to promote it have failed. They should be better, encompassing not only ‘education’ (this is how you ‘latch’ a baby), but economic support. (Wages for breastfeeding.) But, more urgently: bring back National Milk.3

Bring back National Milk. Use the authoritative blue and white of the NHS to reassure parents that the cheapest option can be the best. Better yet, put the NHS logo on it (god knows it has been put on enough other things recently) and offer people a credible alternative to branded formula. Make safe, non-profit infant formula accessible to all carers of all genders and abilities. Remove the financial and physical barriers to infant care. It is always appropriate to offer the bottle.

v. like, of course, Sarah Knott’s Mother, an unconventional history

So much great stuff about tradwife trend written recently: my fave is probably Meg Conley on evangelical prarie dresses and Anne Helen Petersen on the Nap Dress

This great essay on the logistics of bringing back National Milk is very very worth reading